What's Luck Got to Do With it?

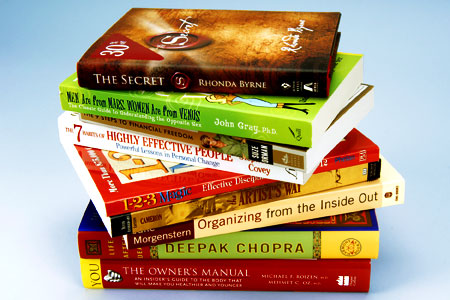

So there you are heading off on your holidays again. But as you while away your time at the airport, you are inevitably drawn to the bookshelves in search of some reading for the plane or the beach. And there they are, those faces smiling out at you from the business and self-help sections. The captains of industry, the motivational speakers, the self-help gurus telling you how you too can have anything you want if you learn their ten steps, seven habits, three secrets or whatever. But while some of these writers have had stellar careers, do they really have significantly more ability than you or have they just been very lucky?

The relative importance of the roles played by ability and luck in organisational and individual success is a question that has been around for a long time. And as we have witnessed the collapse of a variety of organisations recently, some would find it reasonable to speculate that their early successes may just have been a matter of being in the right place at the right time rather than any great ability. The protagonists involved might counter that they were highly skilled but just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time when it all went pear shaped. So which is it?

A recent study by Denrell & Liu sheds some interesting light on this question. Their primary finding is that exceptional performance is not always a good predictor of ability. It is the context in which the exceptional performance was achieved that matters most. If the performance could have been influenced by luck then it is a poor predictor of ability compared with contexts where luck is unlikely to be significant. So an amateur tennis player is extremely unlikely to beat Roger Federer because luck will have relatively little to do with it. However luck kicks in in a big way when chance events can significantly impact on performance such as when future forecasts influence whether professional investors decide to sell, buy or hold shares. Complex systems where components are tightly coupled (i.e. business) are sensitive to chance events and external shocks. So while the business literature loves its heros, you should think very carefully before you decide to imitate Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg or whoever. What’s luck got to do with it? Quite a bit it would appear.

Related articles

John Fahy

John Fahy