What's Your Opinion on Polls?

With election season ramping up in more than one country at the moment you will be hearing plenty about opinion polls as they are gathered, published, dissected and discussed over the coming weeks and months. But just how good are they and what is their track record in predicting what voters actually do?

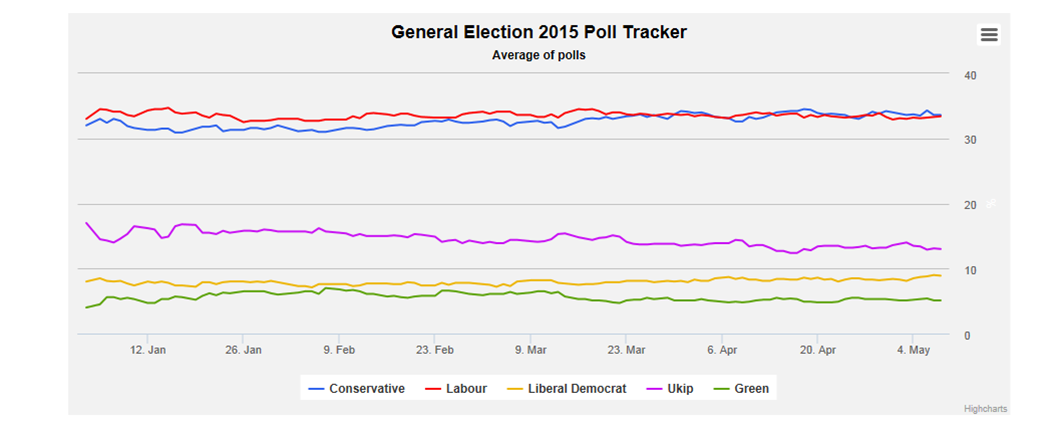

In short, opinion polls often get it right but they also frequently get it badly wrong. The most recent case in point was last year’s British General Election. In the six months running up to that vote, a total of 230 opinion polls of voters were conducted by a variety of research organisations and published in a range of media outlets. The overall trends in the polls are shown below and from about mid-March onwards we see something of a dead heat emerging between the two main parties, the Conservatives and Labour. Of the last twenty polls taken before that election featuring voter samples ranging from 1,001 to over 18,000 people, eight predicted a tie while a further seven gave either side a one per cent lead. Every indication pointed to a really tight race but the actual outcome was a comfortable win for the Tories.

The results of the obligatory inquiry into this failure were published last month. It found that the probable cause was an under-representation of certain groups of voters such as over-70s, under 30s and ‘busy’ voters in certain types of polls that were conducted. Carried out on behalf the British Polling Council – an organisation with a major vested interest here, a methodological failure was probably the lesser of two evils, though an inability to construct representative samples is a pretty damming criticism. The more significant issue of course is that opinion polls in particular and market research more generally are very poor at predicting what consumers will actually do at some future point for a whole variety of psychological reasons. So enjoy all the prediction and discussion and let’s see if anyone can call it correctly this time!

Related Articles

John Fahy

John Fahy